40 minutes by train from central London, near the town of Milton Keynes, is Bletchley Park. If you’ve seen The Imitation Game movie, you’ll know Bletchley Park was a WWII site where secret codebreaking work was completed.

Some estimate this decoding of Nazi radio transmissions shortened the war by years and saved millions of lives.

The grounds of Bletchley Park are very scenic, and the old mansion in the middle remains from before the land was purchased by the UK government just prior to WWII. They wanted a location convenient to London that was non-descript enough to avoid attention from German bombers.

Tucked around the more significant sites was this old abandoned shed.

In the visitor’s centre there is a statue of Alan Turing made of small pieces of flat stone.

Turing was a pioneer of computer science, and I remember learning about him during my first weeks of my computer science courses back in the 90’s. His efforts were crucial to the WWII codebreaking success, though the success was more of a team effort than the solo one portrayed in the Imitation Game movie.

During the war, dozens of huts and additional buildings sprung up around the original Bletchley Park mansion, all containing offices and work rooms. Turing’s office was on the right, behind a bike shed. He routinely biked around Bletchley Park and the surrounding town — sometimes while wearing a gas mask, which he believed helped his allergies.

We were able to wander through a recreation of Alan Turing’s office.

Turing was notoriously eccentric — paranoid of having his coffee mug stolen, he kept it chained to a radiator.

We toured other offices in the huts, restored to their WWII state. At the peak of the war about 9,000 people worked at Bletchley Park, around the clock in shifts.

The vast majority were young women, recruited out of school as teenagers. Many worked on tedious, complicated numerical tasks for hours every day without even being made aware of the overall purpose or how it all fit together.

It was not until the 1970’s that those involved in the codebreaking were allowed to talk about it — many had already died without ever being able to share the role they played in the war even to their own families.

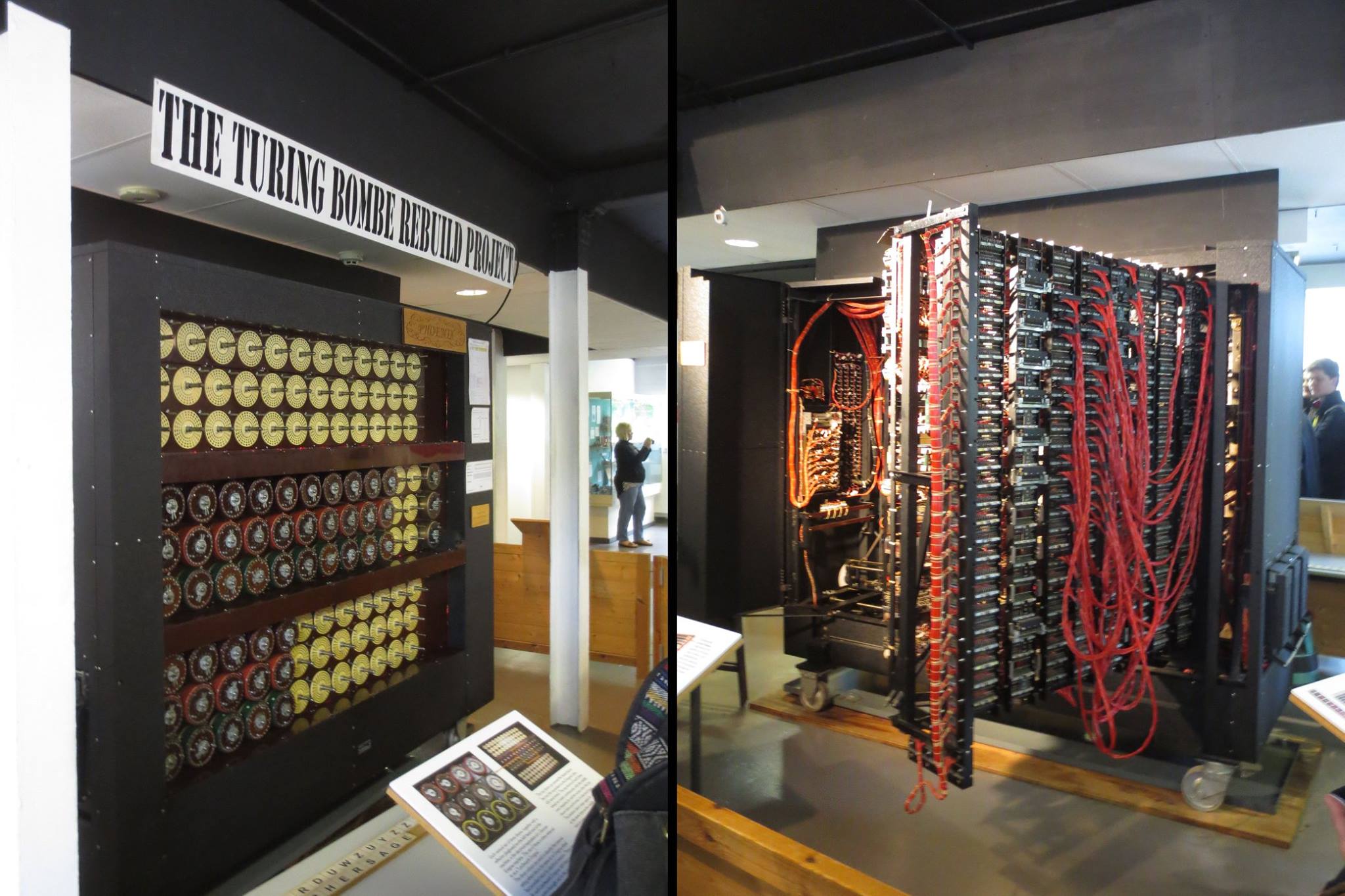

A highlight of the visit were the enormous and noisy “Bombe” machines. These mechanical computers were run daily to cycle through tens of thousands of possible number combinations to figure out the settings the Germans had used that day on their Enigma machines.

Finding the right settings enabled messages from that day to be decoded, until midnight, when the Germans would change the settings and the process would repeat.

This woman gave a long and detailed demonstration of the bombe machines and how they were used. I didn’t understand it all but I appreciated that they didn’t try to dumb things down too much. This machine was a working replica and she fired it up several times, which filled the room with whirring and clacking as the dials turned systematically.

A garage on the property stores historic vehicles, some loaned by Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones, who is apparently a fan of Alan Turing and the Bletchley codebreakers. Jagger produced a movie in 2001 called Enigma that was more factually accurate than the more recent Imitation Game movie.

Our friend Ana took a photo of me and Josie in the fake bar set from the Imitation Game movie. Sadly there was no beer in the glass.