We visited several historic churches while in Spain but the Basilica de San Juan de Dios in Granada was easily the most astonishing and, in some ways, horrifying.

San Juan de Dios (Saint John of God) dedicated much of his life to performing charitable acts for the poor. In 1757, about 50 years after he was canonized, this Baroque church was constructed and his body was moved there.

The religious order he founded remains active, and even today the church is adjoined to a modern medical clinic and a soup kitchen. The Basilica costs only 4 euros to visit, and unlike some churches, photography is permitted, even with flash.

In some contrast to Saint John of God’s aim of helping the poor, the interior of his Basilica is richly decorated with lavish decorations on every possible surface. Gold is the bling of choice, but silver, jewels, carvings, and paintings by famous master artists are also deployed generously. The entire place shines and glistens. Our eyes had difficulty deciding what to focus on.

The towering main altar is the first thing we noticed, followed by the domed ceiling, the organs, and the balconies high along the sides. Around the main floor are smaller side chapels dedicated to different religious figures, some of them elaborate enough to be main altars in a normal church.

Somewhere in all this was another alarming sculpture of the decapitated head of the John the Baptist, a depiction we’d first encountered at the Museo de Bellas Artes on our first night in Seville, and then several more times after that. The Spanish definitely like some gore in their art and religion.

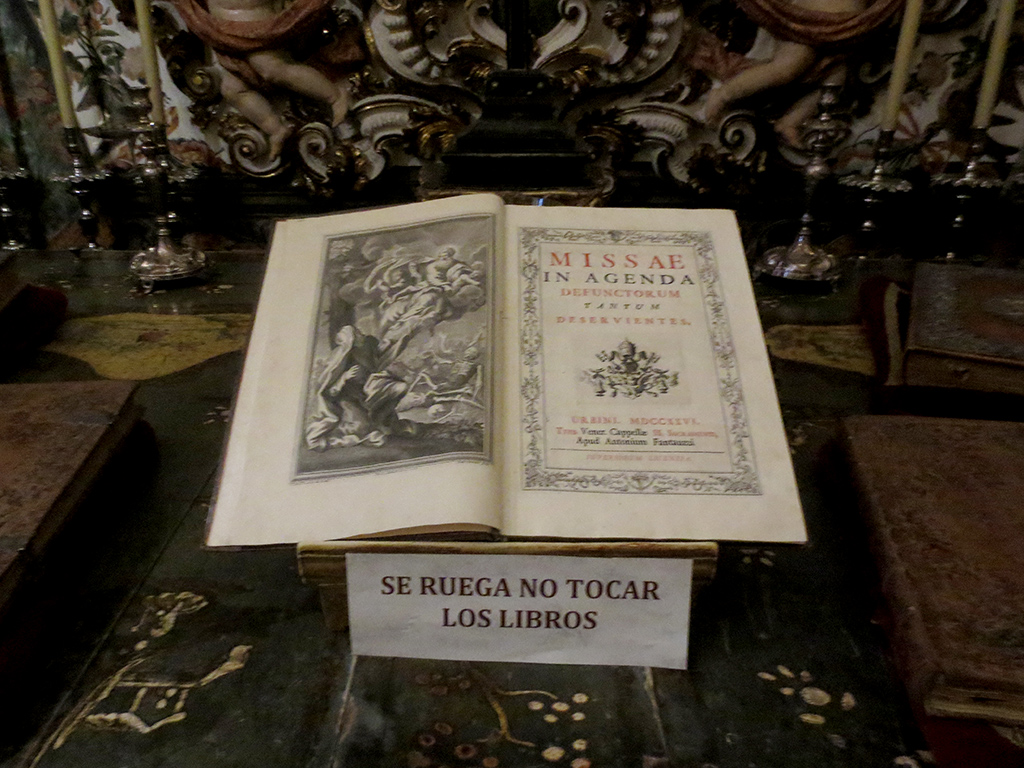

We used the audio guide as we toured the church in the prescribed order, but there was so much to see and the audio progressed from one element to another so fast that I often had no idea which saint, painting, sculpture, relic or architectural feature the British-accented commentator was talking about.

Nobody asked my opinion, but I found the obscene amounts of gold used to honour someone for helping the poor quite confusing, especially when I wondered how much of it originated in South and Central America, where countless thousands died so the Spanish could get their hands on it. The phrase “misallocation of resources” comes to mind.

The most unusual aspect of this church, however, came after we’d completed the tour of the main level. Knowing there was supposed to be access to the upper level, we headed back to the woman at the desk who’d let us in. She quietly took us through a side door and up numerous stair levels where we were able to go behind the altar to enter the giant recessed alcove that could be seen from the ground floor.

In this dizzying area, overlooking the church from above, there is an enormous Camarín Reliquary which contains the relics of Saint John in a huge silver urn decorated with carvings of events in his life.

These “relics” refer to such things such as a thorn from the crown that Jesus wore while being crucified (no doubt) and a piece of the original cross (of course). More gruesomely, they also include shards of bones, some teeth, and even an entire thumb bone of a saint.

All this seemed creepy enough until I turned around and found myself at eye level with various glass boxes on the wall around the Reliquary. These contain entire skulls and crossed bones from various other saints.

One saint was a very humble man who spent his days begging for donations using a woven basket. His tattered basket was displayed without any irony in not-so-humble surrounds.

After about 40 minutes in this church, I started to feel claustrophobic in the small and oppressively decorated spaces. Then I experienced brief terrifying vertigo looking over a knee-high and fragile 300-year-old railing down to the stone floor several stories below.

I’m glad we had a chance to see this astounding building, but I was even happier to leave it behind.