Only five minutes from our apartment there are multiple sets of stairs that lead up into Filopappou Hill. This vast hill is an unfenced and somewhat wild park that is dotted with numerous historically significant ruins and other sites. We’ve already wandered through parts of it several times and there is still more to see.

One route up into the hill passes by the Church of St. Marina, which I feel would would look better without the barbed wire fence. This relatively new church was built atop the foundations of several generations of older churches including a Byzantine church dating to the 11th century.

Part way up the hill we passed this tour guide, a young man with impressive curly hair and beard worthy of Socrates. He was explaining the significance of the site to a young woman. Filopappou Hill is generally recommended as a great place to find views of the Acropolis and this proved to be very true.

Mixed among various pine trees are many olive trees. If left untrimmed these trees become very gnarled and interesting as they grow old — some can live for centuries.

Not far away is the Pynx, which looks at first glance like a long stone cliff dug into part of Filopappou Hill.

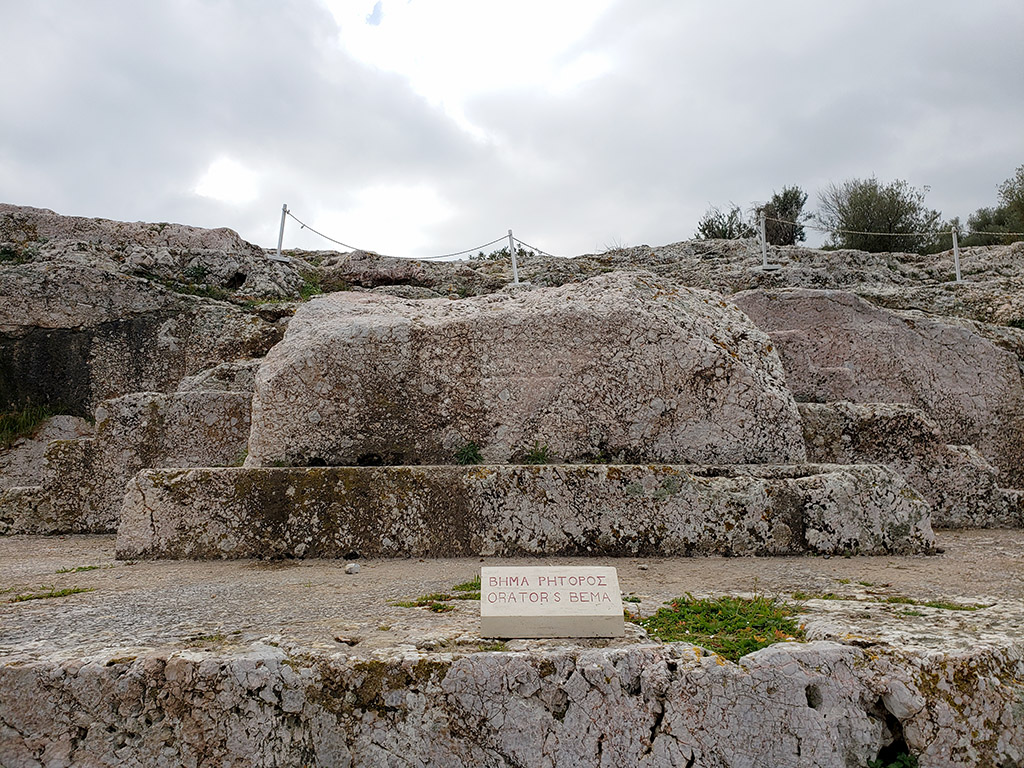

The Pynx is actually a significant excavation that reveals the remains of the place where Athenians gathered to participate in some of the first examples of democratic government in human history. This site was in use from approximately 500 BC until 100 BC, and it consists primarily of an oratory platform (called a bema) from which a speaker could address crowds of up to 15,000 people gathered on the facing slope.

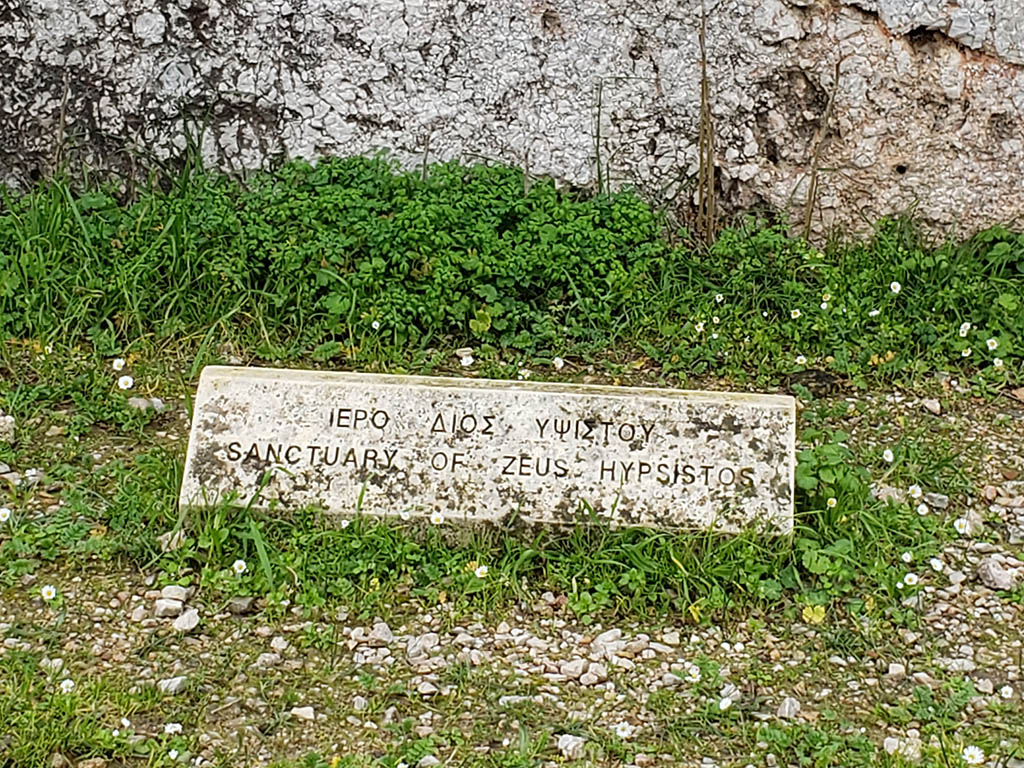

The site of the Pynx was later repurposed by the Romans for use as the Sanctuary of Zeus Hypsistos, a sort of shrine to honour the god Zeus. Numerous niches carved into the face of the rock likely once held statues of Zeus along with other sacred items.

Not far away we found the very unusual Church of St. Demetrius Loumbardiaris, a 12th century Byzantine church that was remodeled extensively in the 1950s and 1960s by architect Dimitris Pikionis. This remodeling gives the surrounding yard something of a Frank Lloyd Wright ranch house vibe, which I found oddly appealing.

The inside of the church is pure Byzantine, however, with a single stone vaulted aisle that provides the impression of being inside an ancient cave. There are also some nice fresco paintings on the side walls dating to the 1700s that were too dimly lit to photograph.

Outside the church some bells hang on a standalone frame that seems more reminiscent of a Japanese Shinto shrine than a Greek church.

Even in between the churches and archeology, the paths around Filopappou Hill are beautiful even in winter. Many of the trees and plants maintain their greenery — I can imagine this hill being much more lush in shoulder seasons, but also hot and parched at the peak of an Athens summer.

The last sight we came across in Filopappou Hill has the most evocative name — Socrate’s Prison. The name derives from the idea that this is where the philosopher Socrates was imprisoned before going to trial for corrupting the minds of Greek youth and failing to express belief in the official gods of the state. He was sentenced to death by drinking a poison made from hemlock.

These events did take place near here, and these rooms carved into rock definitely do look prison-like with their modern metal bars. But apparently archeology shows that this was not a prison at all. Instead it formed part of the foundations of a larger building constructed around 450 BC from wooden beams that protruded from the square notches above the doorways.

This area did play a factual role in more recent history. In WW2, when it became clear that Greece was going to be invaded by the Germans, museum workers hid many valuable artifacts in these caves behind cement walls to prevent them from being plundered by the Nazis.