Knossos is an archeological site located in Crete just outside the capital city of Heraklion. The palace complexes built here by the ancient Minoans peaked around 1700 BC with a population of over 100,000 residents.

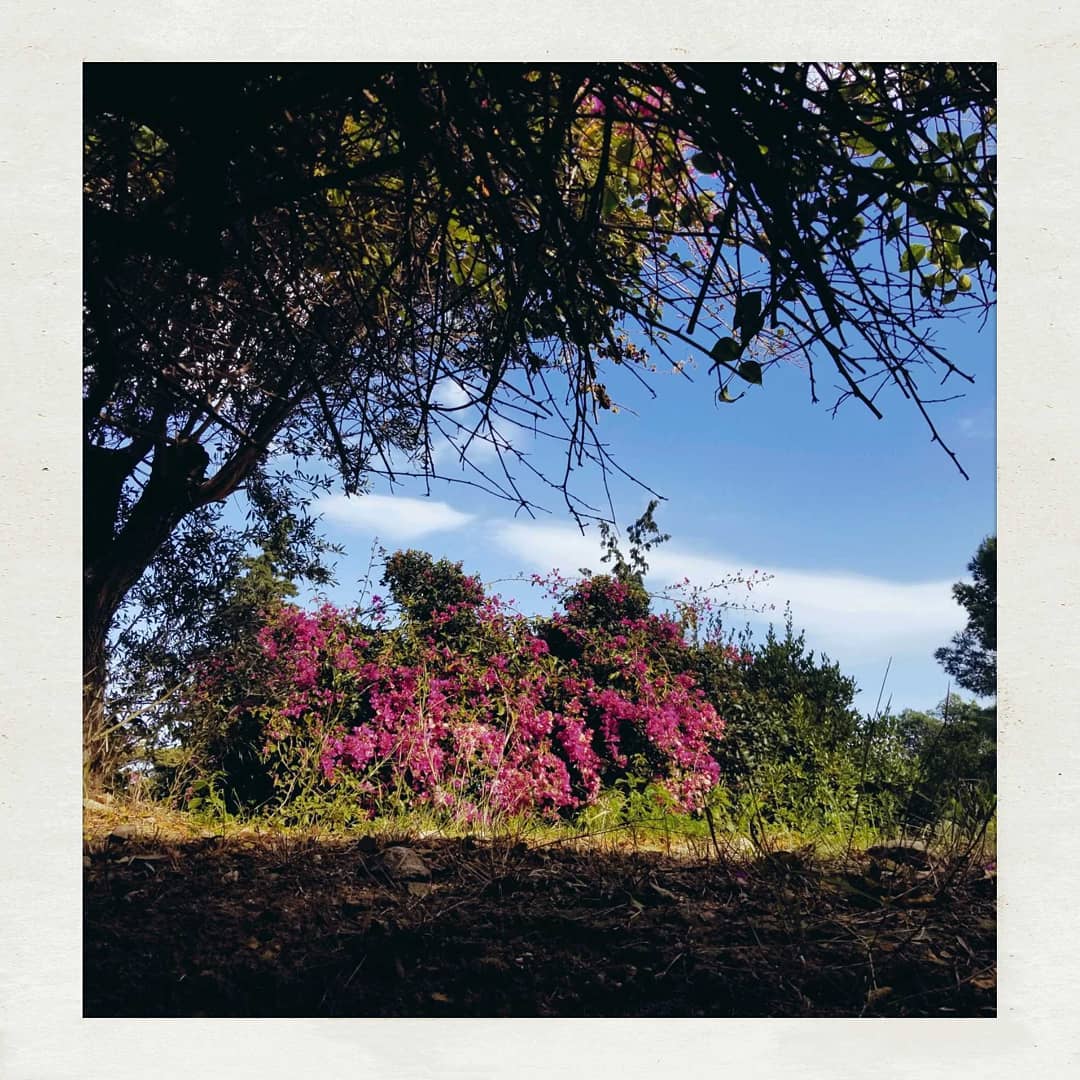

After an uneventful 25-minute ride on a Heraklion city bus through modern suburbs, we abruptly reached the more rural surroundings of Knossos. We entered the archaeological area through a pleasant covered walkway.

It was a warm day for February, with the temperatures quickly rising into the high teens. Bright pink bougainvilleas were in full bloom.

One of the first things to greet us inside Knossos was a bust of Sir Arthur Evans, the controversial British archaeologist behind the original excavations of the site that began in 1900.

Evans made many assumptions about the finds he unearthed, labeling areas of the complexes in ways that have not stood up to modern research.

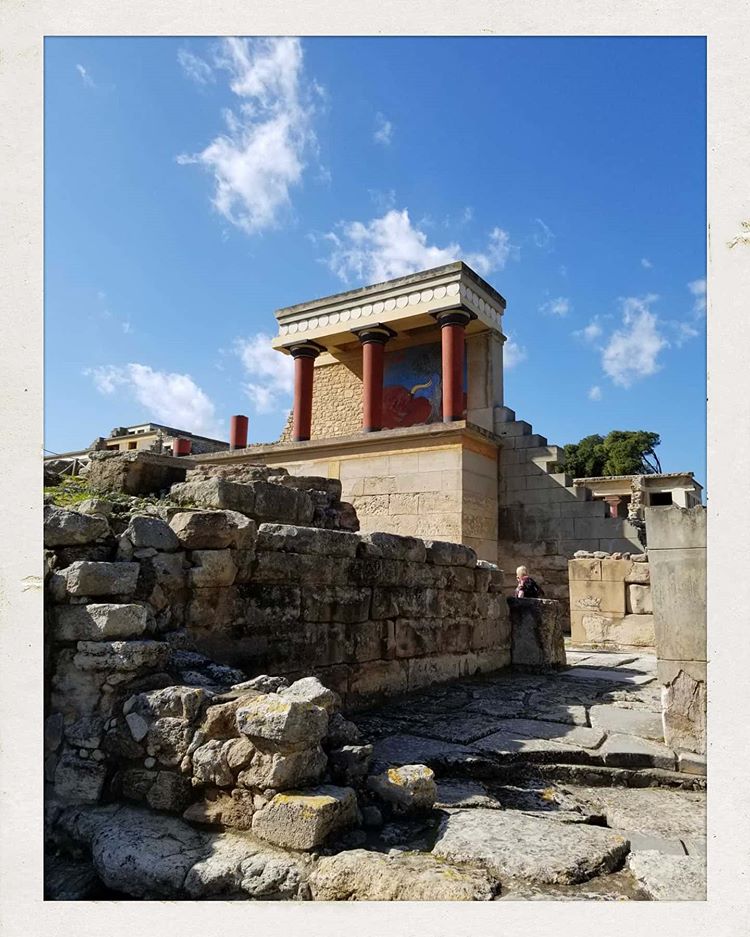

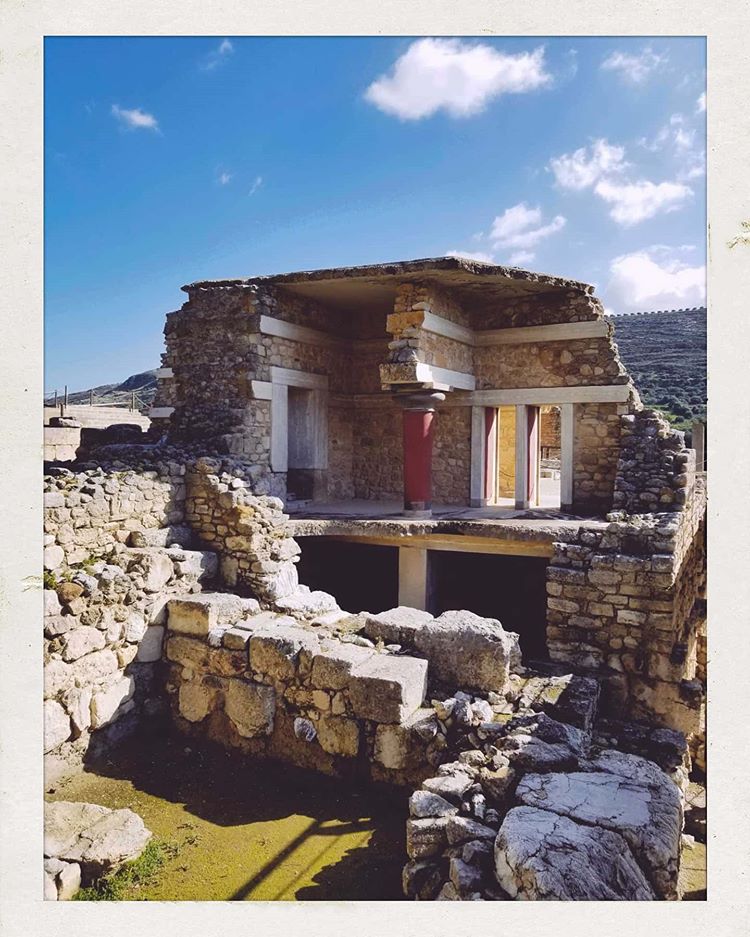

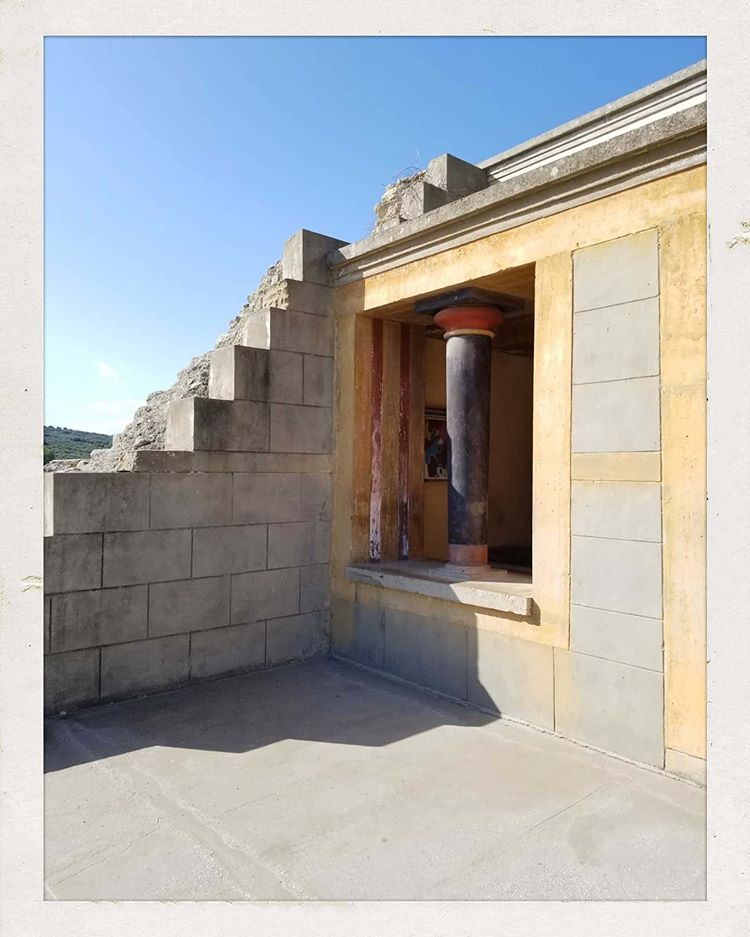

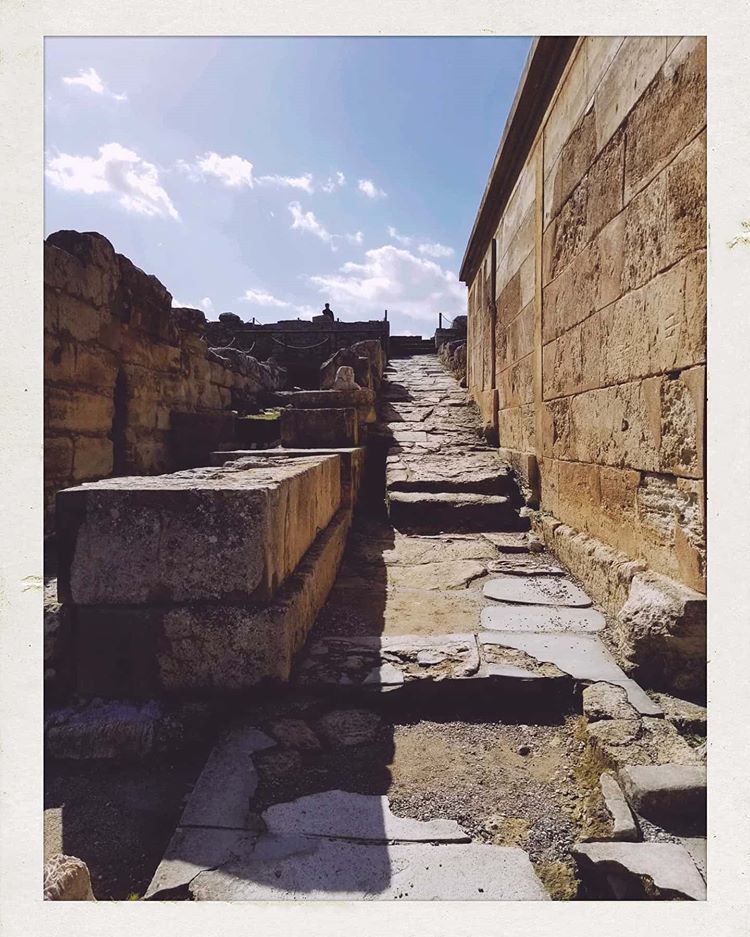

Worst of all, Evans had significant portions of the complex “reconstructed” in concrete, permanently covering archaeology with modern structures that fit his personal theories.

The distinctive painted pillars are authentic to the Minoan palace, however, they would have been made out of wood, not concrete.

On the ground, some areas reveal the difference between the original floor surface and the modern concrete one that overlays it.

Similarly, there’s one pillar that makes clear how much of the original pillar was excavated, and what was built on top of it. The metal cage is presumably to keep the original base from crumbling completely under the weight of the concrete above it.

Knossos is also known for its elaborate and colourful fresco wall paintings. These were also discovered in very fragmented form and later reconstructed, with Evans’ guidance, by modern painters who incorporated varying amounts of creative license.

(The murals shown at the archaeological site are replicas; the originals are in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum, which we visited later in the day.)

At the heart of the palace complex is what Evans labeled the Throne Room. The specific interpretations are disputed, but the current reconstruction shows a carved stone throne adjacent to a stone basin (presumed to be used for vague “rituals”) and stone benches for visitors attending.

One other significant reconstruction on the site are the large concrete Horns of Consecration. These horns were a common symbol in Minoan civilization, and we saw many smaller authentic examples of them in museums around Crete. Bulls were significant to the Minoans, and from them come King Minos (the first king of Crete) and the mythical Minotaur.

We personally found all these reconstructions a bit frustrating to understand. It is difficult for the average person to distinguish where factual ancient history ends and a 1920’s-era fantasy begins.

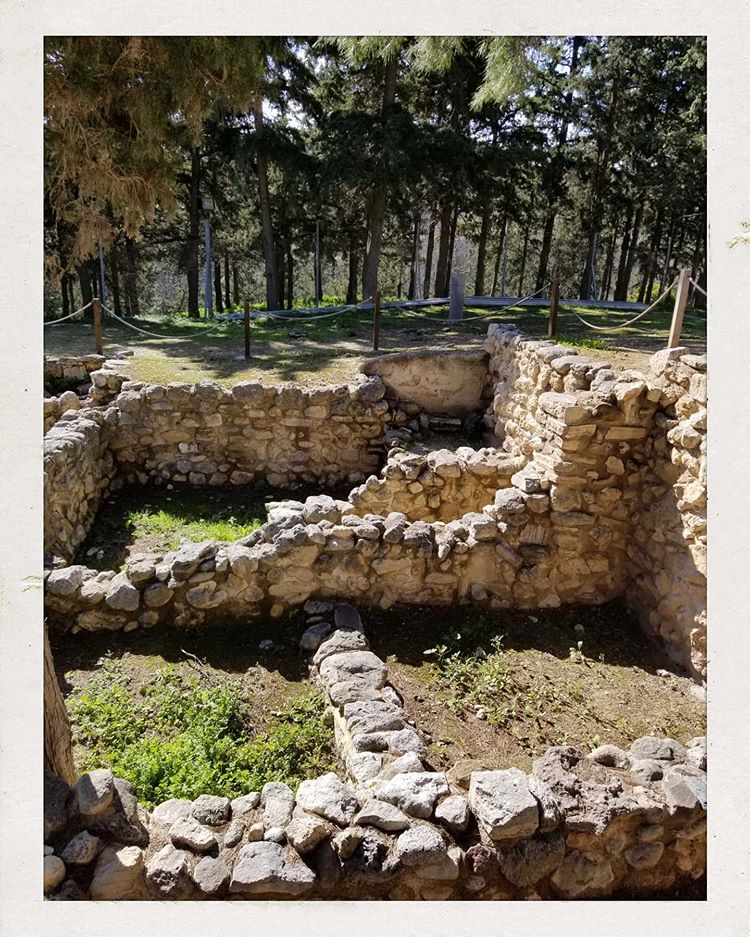

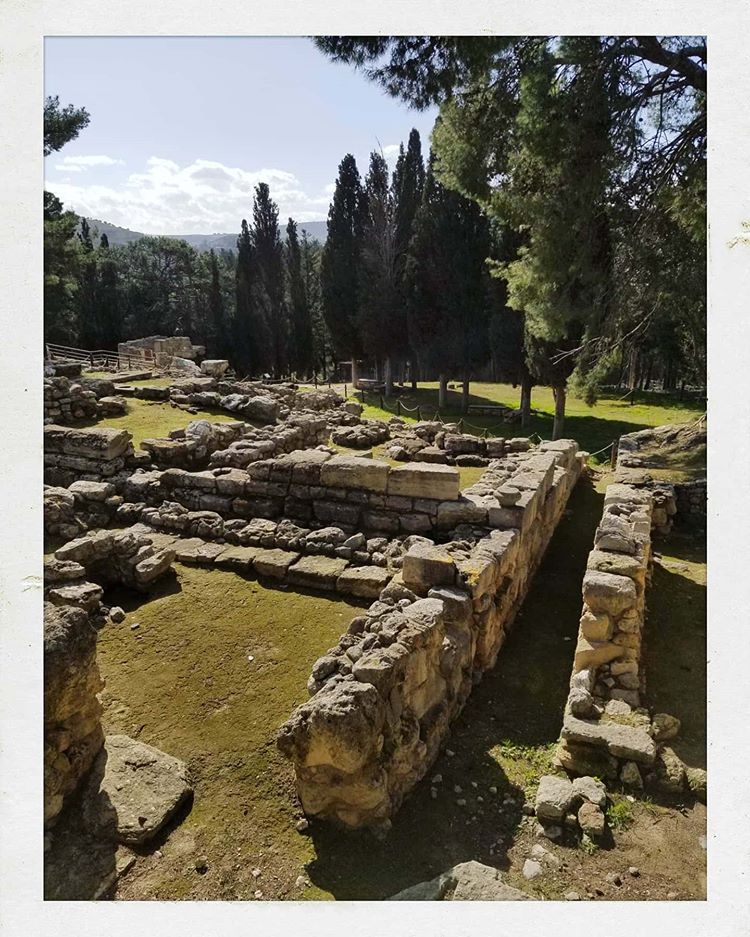

Thankfully, there are large areas of the Knossos site that have not been aggressively reconstructed, but merely excavated. These were more evocative and the surrounding hills and nature made for a nice place to wander. Occasional signage explained the significance of specific structures.

The Minoan palaces at Knossos were active until around 1100 BC, when they were abandoned. Reasons for the abandonment are still disputed, but theories include major earthquakes and gradual incursions of Mycenaeans from what is now mainland Greece.