The Greek island of Delos sits at the center of the Cyclades. The island held great importance to both the Ancient Greeks (as religious center) and the Romans (as a commercial port). Today the island is an uninhabited archaeological site that can only be visited during limited hours. Staying overnight or swimming on Delos is forbidden.

Since we were staying on Naxos, the best way to visit Delos was by a one-day cruise that also stopped at nearby Mykonos. We departed from Naxos in the morning, picked up some additional passengers at the port on Paros, and then took a one-hour journey to Delos, where we had three hours to explore the site.

Unsurprisingly, a friendly gang was cats was waiting near the ticket booth to greet those arriving from the boats.

Once we managed to navigate the somewhat chaotic ticketing area and separate ourselves from the tour mobs, the first area of importance we encountered was the Sacred Way, a procession of monuments leading to the sanctuary of Apollo. Delos was considered by the Ancient Greeks to be the birthplace of Apollo, one of their most important gods. This made the island a sacred location for worshippers from across Greece, who would arrive to visit the temples, make offerings, and participate in ceremonies honouring Apollo.

Much like another Sacred Way we walked in Delphi in 2020, this path would have once been lined with ornate templates and monuments constructed by city states and individuals who wished to prove their dedication to Apollo — and also to outdo the others and show off their wealth. One of these monuments is a Portico offered by Phillip V King of Macedon in 210 BC, with engravings of his name still visible today on the remnants.

At the end of the Sacred Way are three marble steps that lead to the Propylaea (entrance gateway) to the sanctuary. Today, the steps are roped off, so we had to walk a route that leads around them.

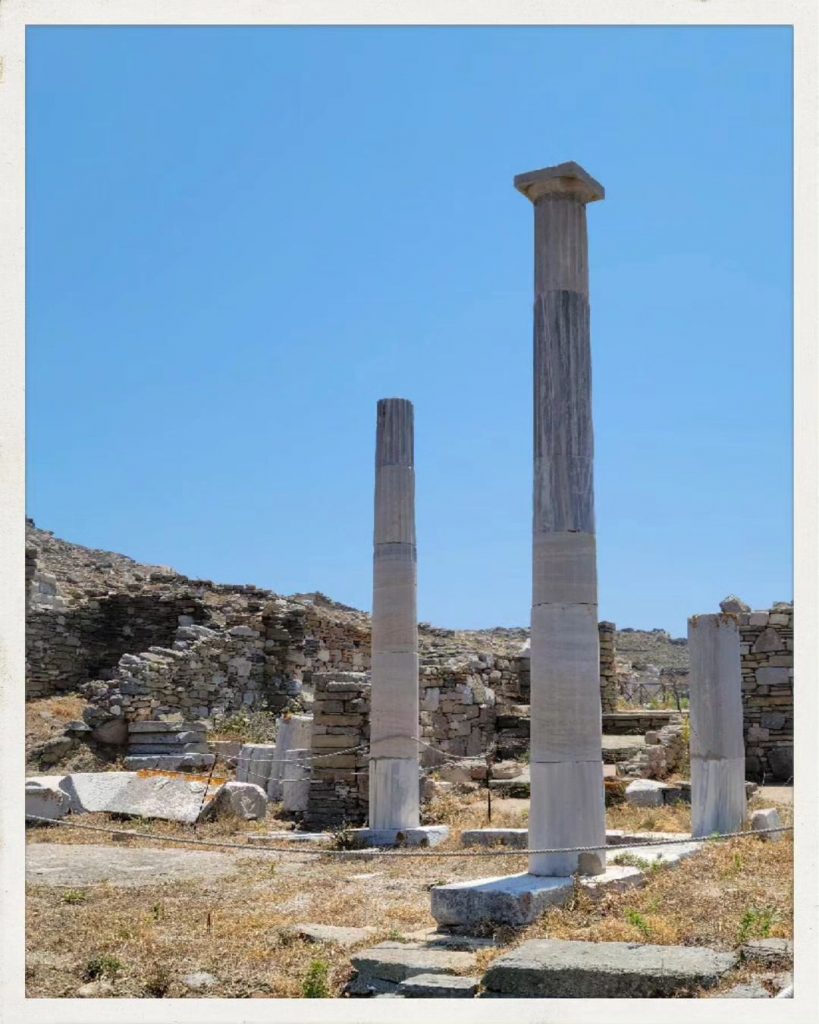

Beside the Propylaea is the House of the Naxians, which has a row of columns down the centre. In the 7th Century BC, the island of Naxos was an economic powerhouse in the region, and this building was one way they demonstrated their power relative to others.

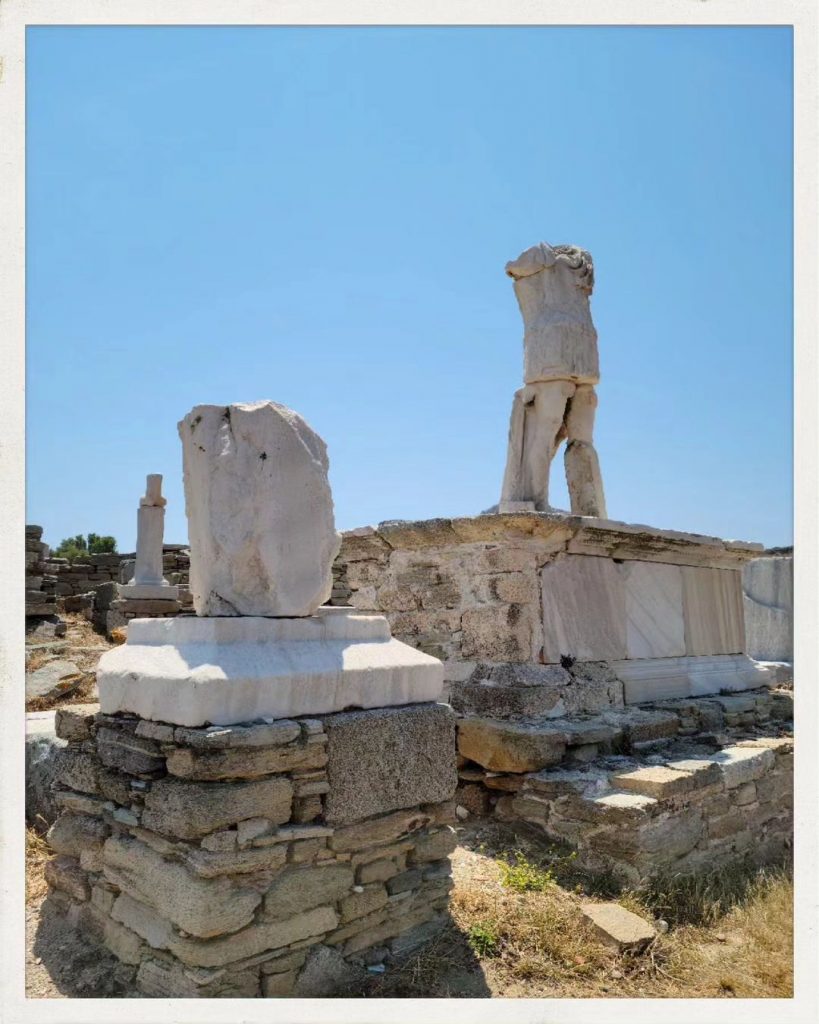

Beside the House of the Naxians is an enormous marble stone that once served as a platform for a colossal statue of Apollo, one that was so tall it could be seen from the sea over the roofs of the surrounding buildings and temples. The front of the platform is engraved with the words “I am of the same marble, statue and base”. The statue was destroyed after 417 BC, and most of the pieces were hauled away in the following centuries — along with many other ancient artifacts that were plundered by visitors who simply helped themselves to whatever they could cram into the holds of their ships. Today if you pocket even a small fragment of archaeology you can be charged.

Beyond the statue of Apollo were three separate temples honouring the god, built by Delians and Athenians. Only foundations and a few pillars remain intact today.

Nearby is the most recognizable imagery from Delos: The Terrace of the Lions. There were originally up to twelve large lion statues, carved in the 7th century BC. In the early 1900s seven remaining lions were excavated and placed on pedestals in what was presumed to be close to their original positions. In 1999, due to ongoing damage by weather, the originals were removed to the museum and exact replicas were placed outside. (The same thing was done for the cartyatids on the Acropolis in Athens.)

Past the lions is the House of the Poseidoniasts, recognizable by a group of standing white marble columns. The Poseidoniasts, merchants from what is now Beirut, worshipped the god Poseidon. This large building served as their living quarters while trading on Delos, as well as a place where they could worship.

Other buildings in this area were used for more mundane purposes, such as homes and workshops. In some of them, there was evidence of archaeologists still at work, in this case presumably sorting bits of stone and tiles into different types.

Roughly in the middle of the archaeological site is the Sacred Lake, drained in 1926 to prevent malaria. The former lake is now a round evergreen grove, bordered by a low stone wall. In ancient mythology this was a shimmering lake that “shone golden” when Apollo was born, and was home to his sacred swans.

At the center of the now-drained lake has been planted a palm tree, which represents the one that Leto (Apollo’s mother) apparently clung to as she gave birth to Apollo. This particular palm looks like it could use some rejuvenation.

Just north of the lake, some archaeologists were at work under a purple umbrella. Aside from the short trees in the Sacred Lake, there’s very little shade on Delos. We were happy not to have ignored warnings from the cruise to come equipped with hats, sunscreen and water. But we didn’t account for the strong winds, which kept blowing Josie’s hat away.

A detailed mosaic floor in a prominent house has been nicely preserved. We could not walk on it, but we could view it through barriers on each side.

At the far end of the site is the Archaeological Museum of Delos, housed in a decrepit bunker of a building. It is currently closed for overdue renovations, so unfortunately we were not able to see many of the more fragile artifacts that have been found during excavations (to compensate for this disappointment, they are only charging about two-thirds of the normal admission price to Delos). I did use the bathroom in the museum, which was open, and it was every bit as unpleasant as I feared it would be.

Josie waited outside with more cats.

From there, we began heading up the path leading to Mount Cynthus. This pointy granite mini-mountain looms above the archaeology, though it’s barely 100m in height. But the hot, dry, rocky environment makes the effort of climbing more gruelling than it might otherwise be. In comparison, Arthur’s Seat, which we climbed in Edinburgh in more temperate conditions, is more than 250m high.

About halfway up, we came across the very attractive Temple of Isis, a Doric temple built in the 2nd century BC and enhanced about 100 years later.

At this time Josie began to feel the effects of the heat and sun, so she decided to wait near the temple while I made the rest of the climb to the top of Mount Cynthus for photos. I was hot too, but having come most of the way I was determined to finish the climb.

The ascent is straightforward, just a long stone staircase, but it’s irregular and slippery in places with many opportunities for a broken ankle.

The views were nice.

Near the summit, people had built small stone stacks, something that’s become a bit of a plague in any touristy place where there are loose stones. I’d prefer to see things left unmodified by previous visitors.

People were taking selfies on the summit, and a group of Japanese tourists (not shown) sat in a circle eating nicely pre-packed snacks.

The Cycladic group of Greek islands are so-named because they form a circle, centered around Delos. From the summit of Mount Cynthus it is apparently possible to see the islands of Andros, Mykonos, Naxos, Paros and Tinos. I could certainly see many islands in the distance, but I could not identify them.

My summit diversion only took about 15 minutes, and I rejoined Josie by the Temple of Isis. She had made productive use of her break by listening in on some of the guided tours passing through and getting some info about what was remaining to see.

Descending through more archaeology, we passed the Ancient Theatre of Delos, constructed beginning in 314 BC and capable of seating 5000 spectators.

From there, it was back down to the port where we’d have a bit of time to rest our knees and recuperate from the sun aboard the boat en route to Mykonos.

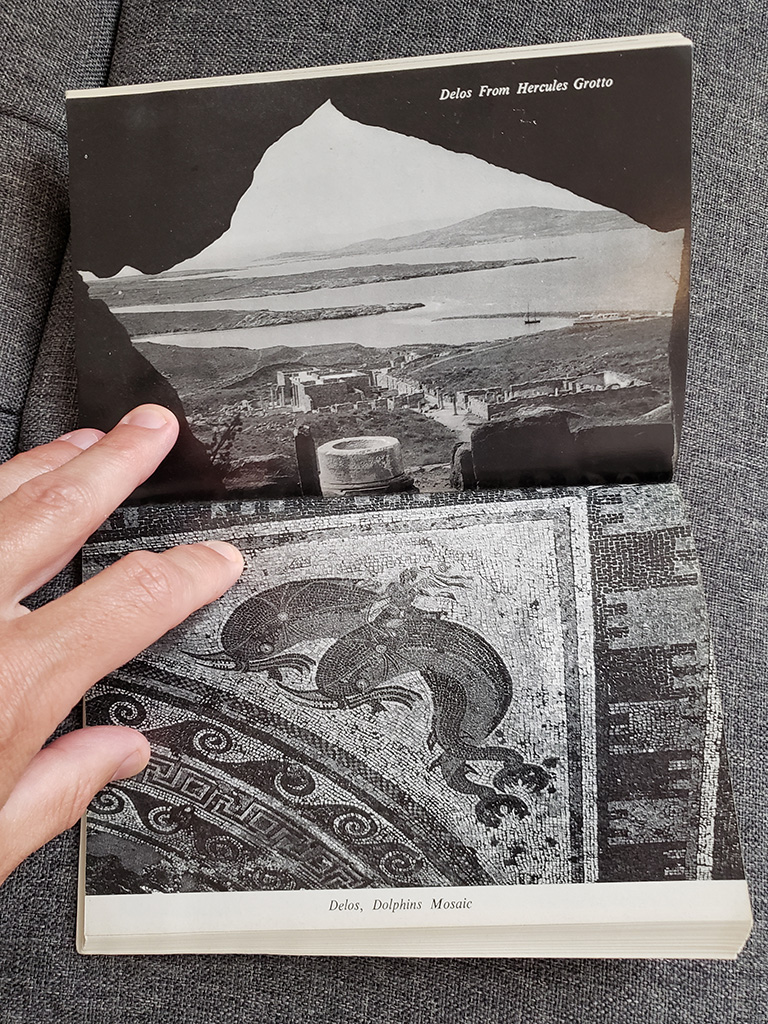

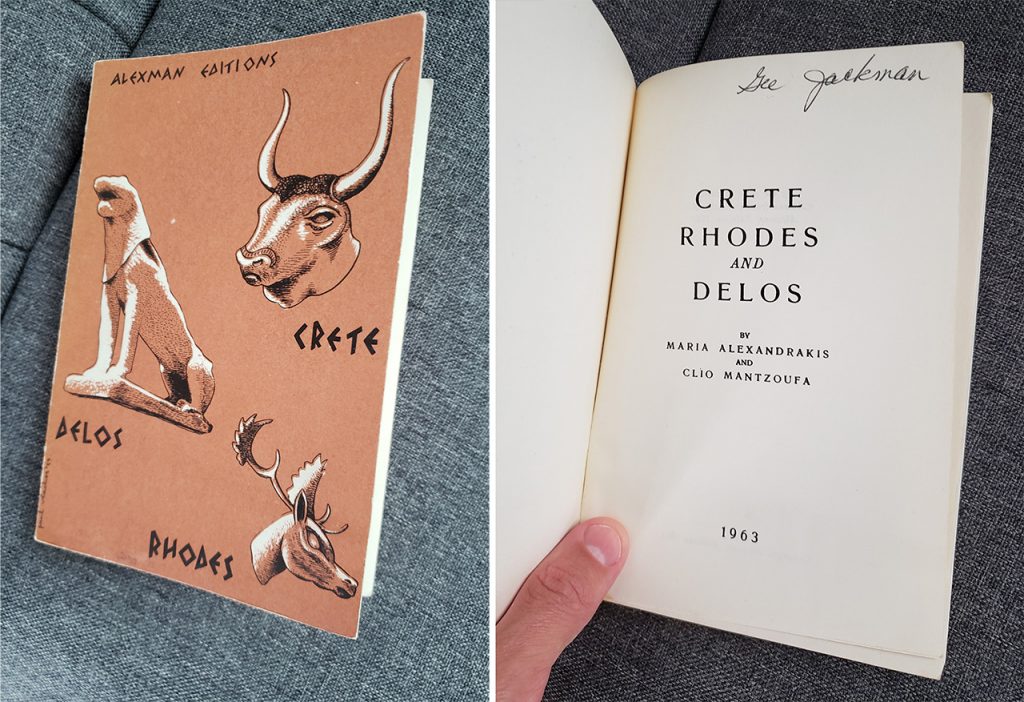

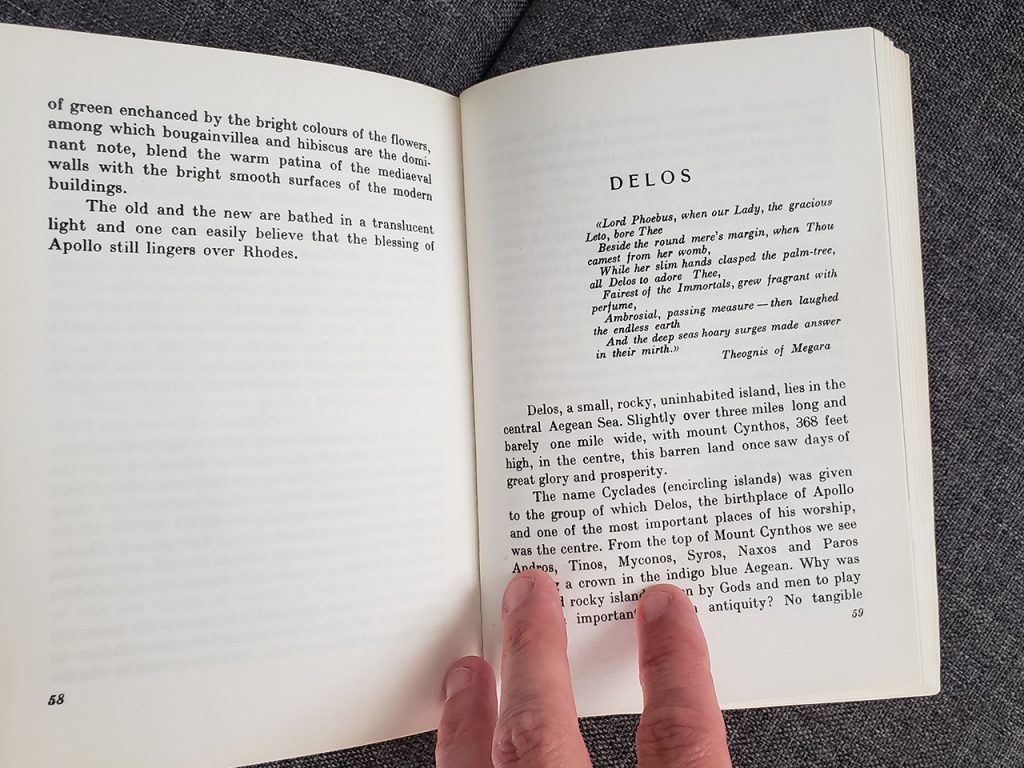

A footnote: Back at home during the pandemic, one of the many random used books I ordered online was this small travel guide to Crete, Rhodes and Delos, originally published in the 1950s (though my edition is from 1963).

I read it, then brought it along out of curiosity, because uninhabited Delos is probably one of the few tourist destinations in the world that hasn’t changed dramatically in the past 60 years. I’m sure ongoing archaeology has refined the understanding of some aspects, and certain areas described in the old guide are (thankfully) no longer accessible for tourists to stomp around on, but on the whole this book was still a good source of information.