Hidden in a complex of tunnels deep beneath the Upper Barrakka Gardens are the Lascaris War Rooms. This once-secret facility was used as the command headquarters for the defense of Malta and the Allied invasion of Sicily during WWII. The complex is now being fully restored and we received a guided tour from a retired member of the RAF.

Getting to the War Rooms was an adventure in itself. Apparently there is a shorter route, but the one we took brought us down at least half a dozen stone staircases and alleyways from the Upper Barrakka Gardens. It did make it clear why the location was a good one for a secret military facility.

The last part of the trek was through a long, straight tunnel. We later learned that the original purpose for this tunnel was to transport navel mines down a rail from the city, where they were manufactured, to the harbour where they could be deployed to defend it.

The entire complex of rooms and tunnels were dug from solid rock. A few tunnels existed from the time of the Knights Hospitaller, but most were dug at the beginning of WWII, by hand and machine but without the use of explosives.

After we purchased our tickets, we were escorted to a small theater room to watch an introductory film about WWII in Malta. This helped provide context for what we would see later during the tour.

The first part of the film was a brief overview of how the war came to reach Malta very early on. It featured some excellent historical footage, much in colour.

This introduction was followed by a film produced by the British Army in 1942 to coincide with the awarding of the George Cross to the citizens of Malta. This film was essentially propaganda, designed to highlight the sacrifices the Maltese had made for the war effort in order to encourage the same sense of sacrifice at home in Britain. For us, we were struck by how much Valletta remains unchanged since that time.

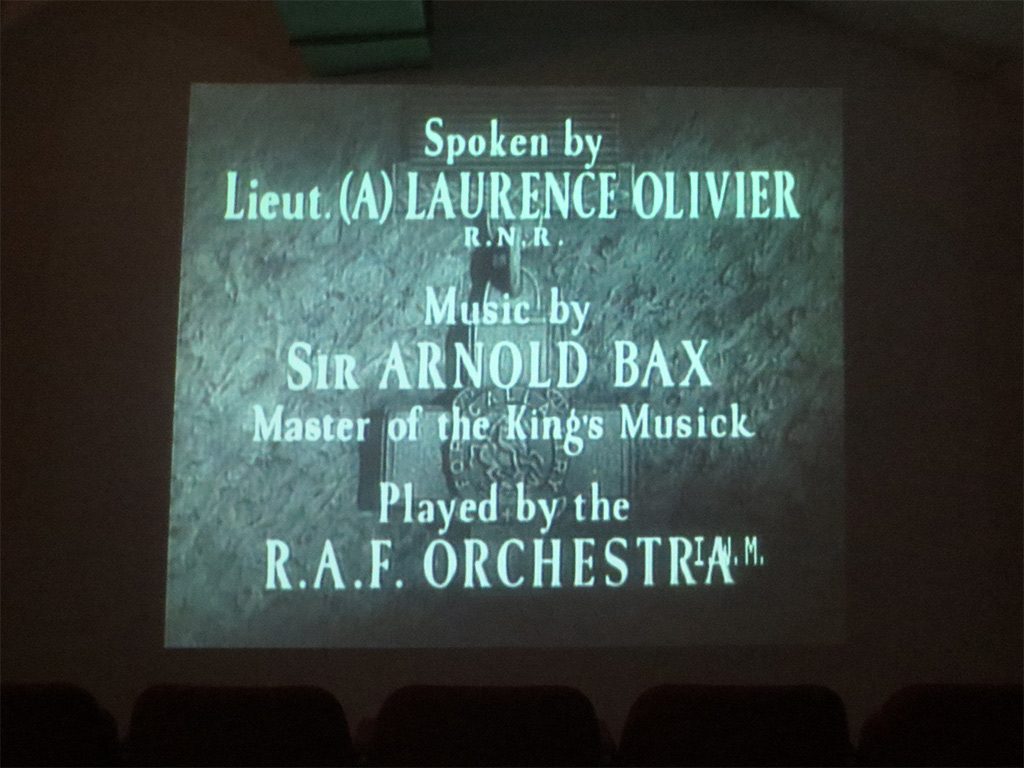

The film, titled Malta GC 1942, is dramatically narrated by Laurence Olivier and accompanied by equally dramatic music performed by the RAF Orchestra. It’s dated but quite effective even today with some stunning footage. It is only 19 minutes long and it is more than worth watching on YouTube.

After the film, we headed down through the long corridor to the far end of the complex, to wait for our guided tour. Our guide was Mike, a former member of the RAF (though not a pilot, he was quick to point out) and he was extremely knowledgeable and enthusiastic. The tour began with just the two of us, though another couple joined partway through.

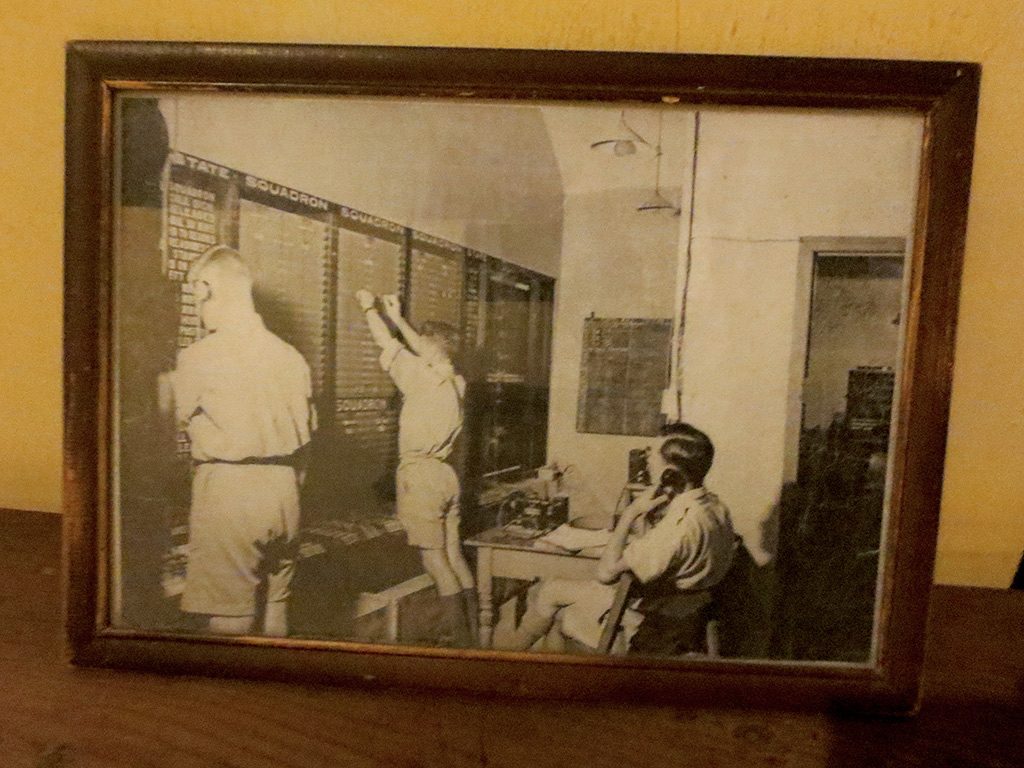

Mike began by explaining the work done in the filter rooms, where young women (and even girls as young as 14) worked shifts. Their job was to ingest information about potential enemy bombing raids that came in from various sources such as radar stations, allied aircraft, and phone calls from the general population. The women working these jobs were civilians, mostly daughters of trusted British military personnel. The men were enlisted military and would do multi-day shifts, sleeping in cots when not working.

All the information coming in would be “filtered” for reliability and then plotted onto giant maps to track potential bombing raids in real time. They tracked the known location of a potential squadron of bombers, the likely number of planes in it, the altitude, and the speed. This allowed the anti-aircraft defenses to prepare or fighter planes to be sent to intercept the enemy before they reached Malta.

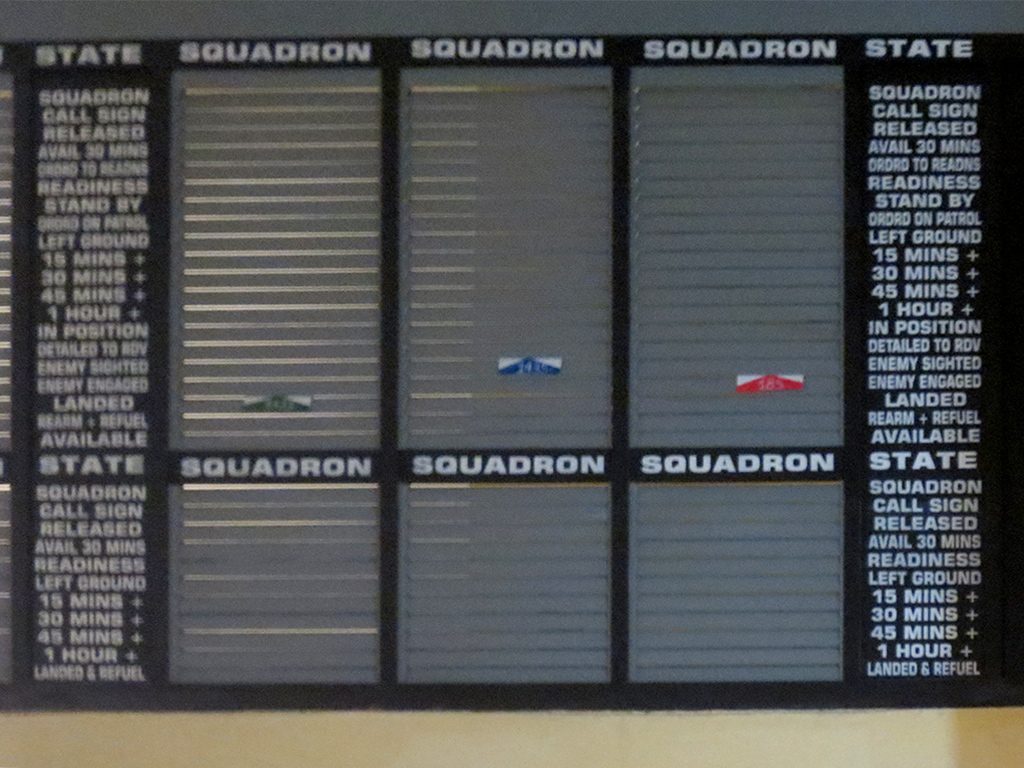

There could be dozens of such events per day, and often many happening at once, so keep all the details accurate was crucial. Each squadron was also tracked on a status board, ironically constructed from the shutters of a bombed Valletta house.

Meanwhile, markers were moved along on a map at 5-minute intervals, showing the squadrons approaching. The spacing and colour of the arrows indicated how fast the planes were going. This alone could help predict what kind of planes might be approaching — fully loaded large bombers were heavy and traveled slower.

All the communications came in by telephone or on headsets, so the rooms would have been noisy with many simultaneous conversations. To reduce the cacophony, many of the phones had their ringer bells installed upside-down, which made them quieter so only the operator could feel the vibration of it ringing at his or her desk.

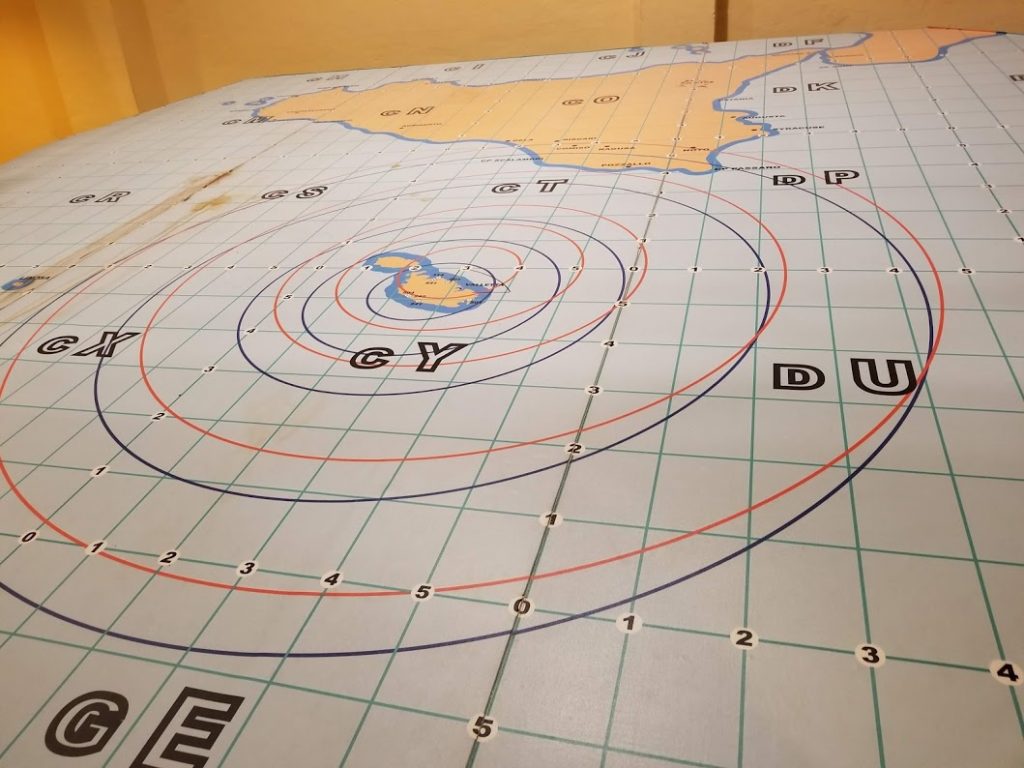

In another room there was a larger wall map that included Sicily.

This is where the “big picture” discussions would be had with top generals. American General Eisenhower and British Commander Montgomery both spent time in this room planning the Allied invasion of Sicily in 1943 known as Operation Husky.

This part of the tour was of particular interest to me as my grandfather was part of that invasion. The Canadians were grouped with the British Eighth Army commanded by Montgomery. Interestingly, throughout the war much of my grandfather’s orders would have likely originated in these rooms, though he would have not known of their existence at the time, and possibly not until many years later.

This map shows the British Eight Army transferring from North Africa (where they had just defeated Rommel’s German troops) before passing through Gozo in Malta and finally landing in Sicily at the town of Pachino. The Canadians apparently joined this invasion via the UK, though at which point is not clear to me.

In the complex there was also a memorial dedicated to one of the women who had worked in the filter rooms when she was young. Marion Childs would have been about 16 when she worked as a plotter. She died last year in her early 90s.

After WWII the complex continued to be used for military purposes, including by NATO during the Cold War, until it closed down in 1977. It is still undergoing restoration and new exhibits plan to open in the future, including one later this year specifically about Operation Husky.